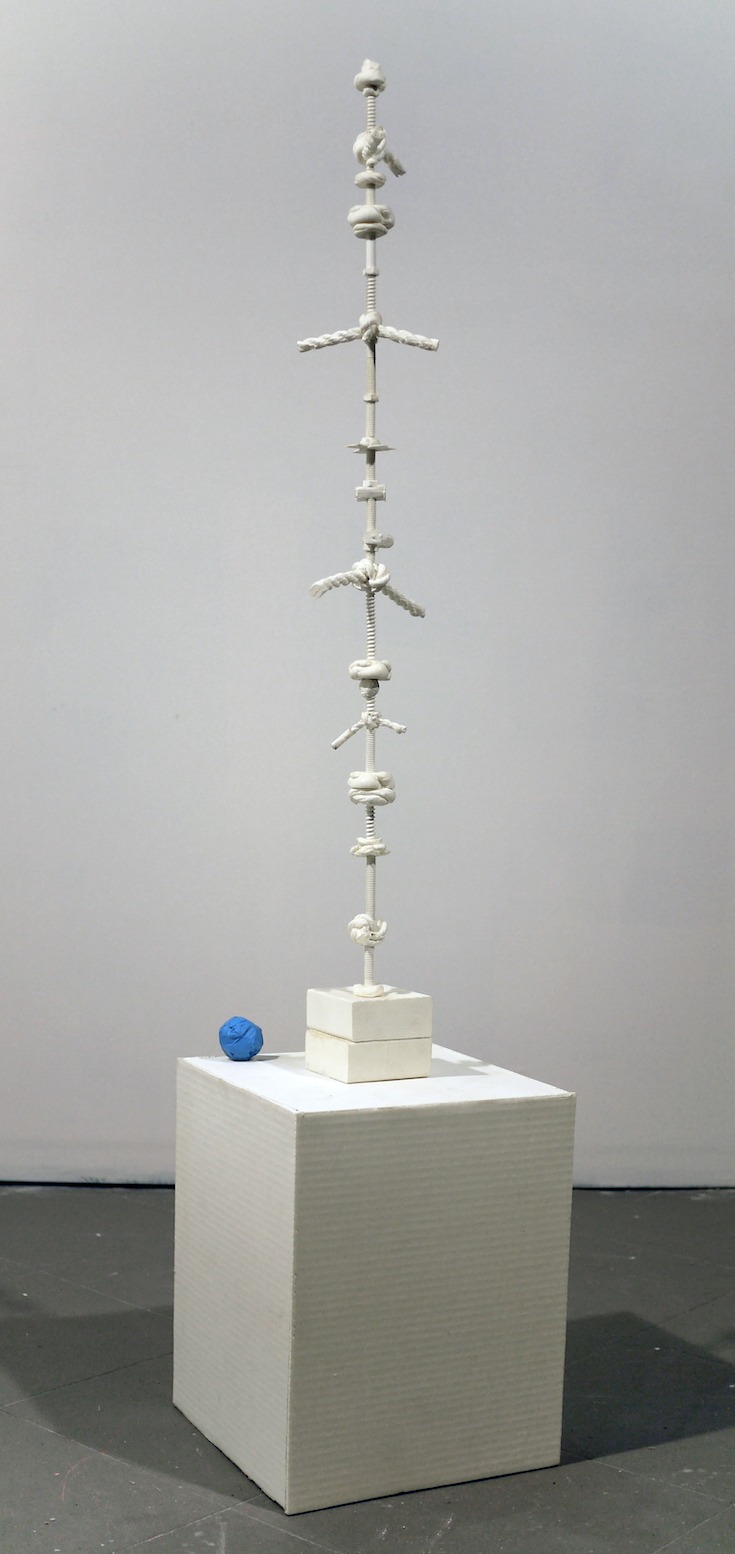

Untitled (Stack) / 2023 / 51 x 9 x 9″ / cast urethane plastic

Untitled (Stack) / 2023 / 51 x 9 x 9″ / cast urethane plastic

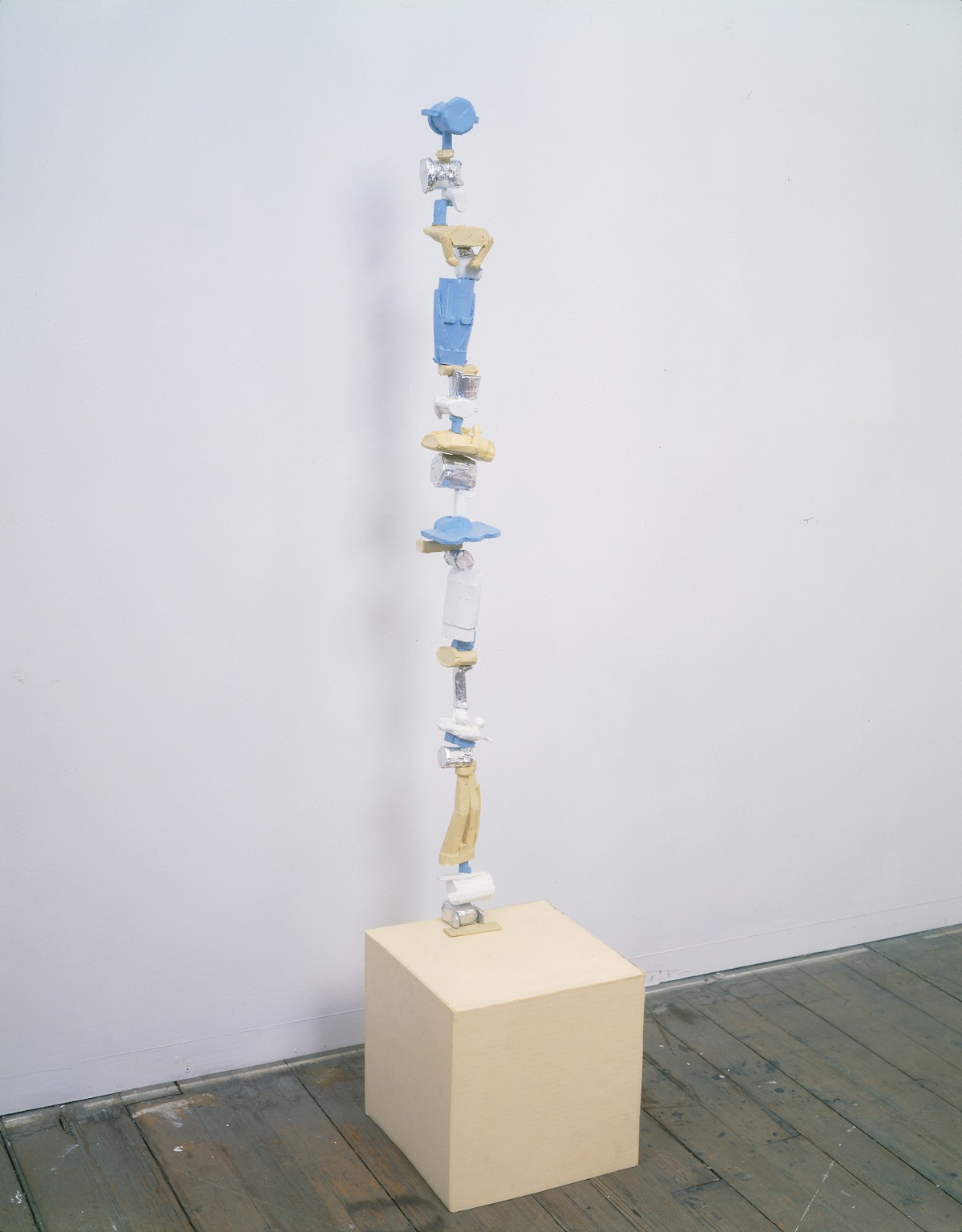

Group view / dimensions variable

Group view / dimensions variable

Untitled (Stack), detail / 2023

I started making sculptures based on kachina dolls in 1987.

It began with a doll I bought at the Brooklyn Museum out of a $1 sale bin, a sagging cardboard box full of 4″ fluorescent orange or green figurines with feathers attached to their heads. These were generic versions of what I thought were Hopi “stomach ache”-style dolls, roughly carved in solid wood and painted with marks bearing no true relation to the coded combinations found on actual Hopi dolls. There was no indication of who had made the objects in the bin or where they actually came from. They seemed to be in limbo. I wasn’t seduced by their forms or tantalized by any idea of them as Other or Outside or Transgressive. For me, the dolls in the bin occupied an awkward space between commerce and culture/s, mutely tragic sculptural objects as a kind of burdened kitsch on their way to becoming something else. The box that contained the dolls was itself a museum within a museum, and variations on the box itself eventually became part of my work.

I made an oversize copy of the doll out of corrugated cardboard and hot glue. I had been working with cardboard for a few years, making large scale, disposable environments. The doll was the first standalone, “figurative” piece I’d made to exist outside of the context of an installation. It was a strange choice, easy to make but hard to fit with either my past or present experience. I remember thinking it was a substitute, hollow and conservative. I was making an artifact.

(text continues after last image) >>>

Statue / 1987 / appx. 8 x 27″ / Cardboard, colored tape, pencil, acrylic polymer and glue

Statue / 1987 / appx. 8 x 27″ / Cardboard, black masking tape, acrylic polymer and glue

Installation View / 1990 / White Columns Gallery, New York

Stack (Wash) / c. 1990 / appx. 33″ w/base / Cardboard, tape, Flasche and glue; wooden dowel armature

Stack (Parti) / Detail / 1988 / Cardboard, colored tape and acrylic polymer on armature

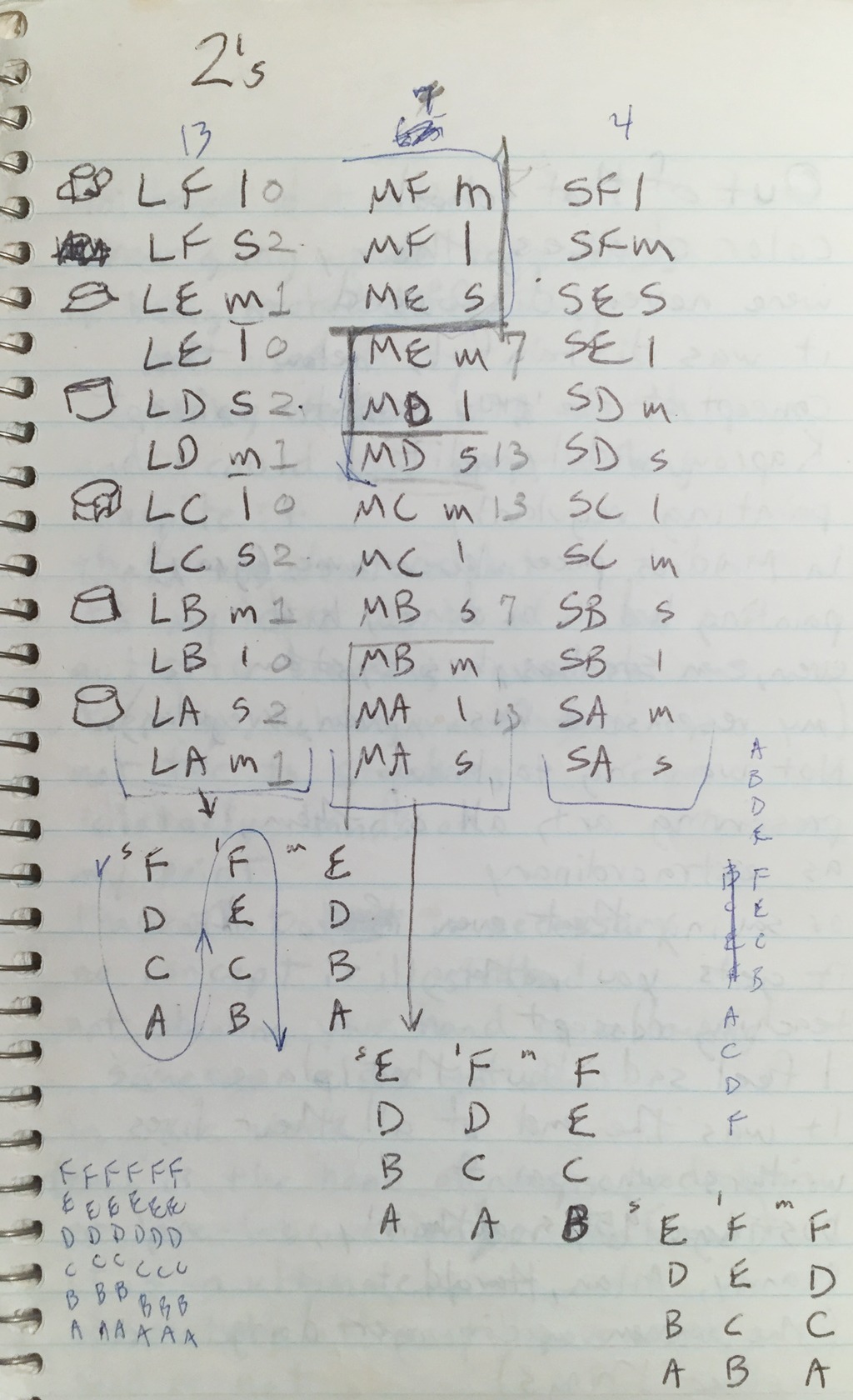

Stack (Pressure) / 1990 / appx. 10″x10″x72″ / Cardboard, paint and acrylic polymer; plywood, steel and copper armature; Stack (Bunny) / 1990 / appx. 14″x14″x75″ / Bare and preprinted cardboard, tape and gloss polymer; plywood, steel and copper armature

Stack (Remainder) / 1990 / (dimensions variable) / Cardboard, tape, acrylic polymer & glue; plywood, steel & copper armature

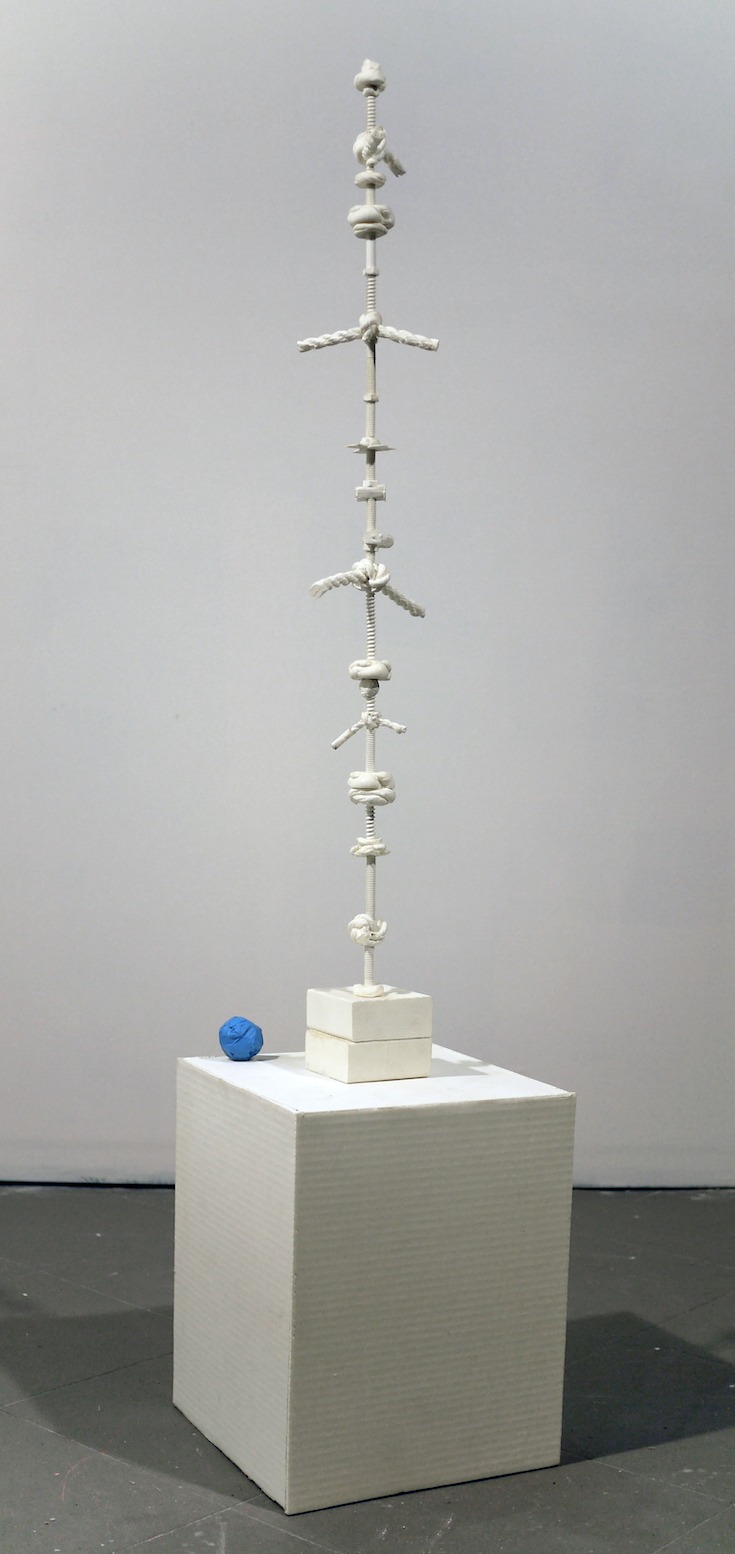

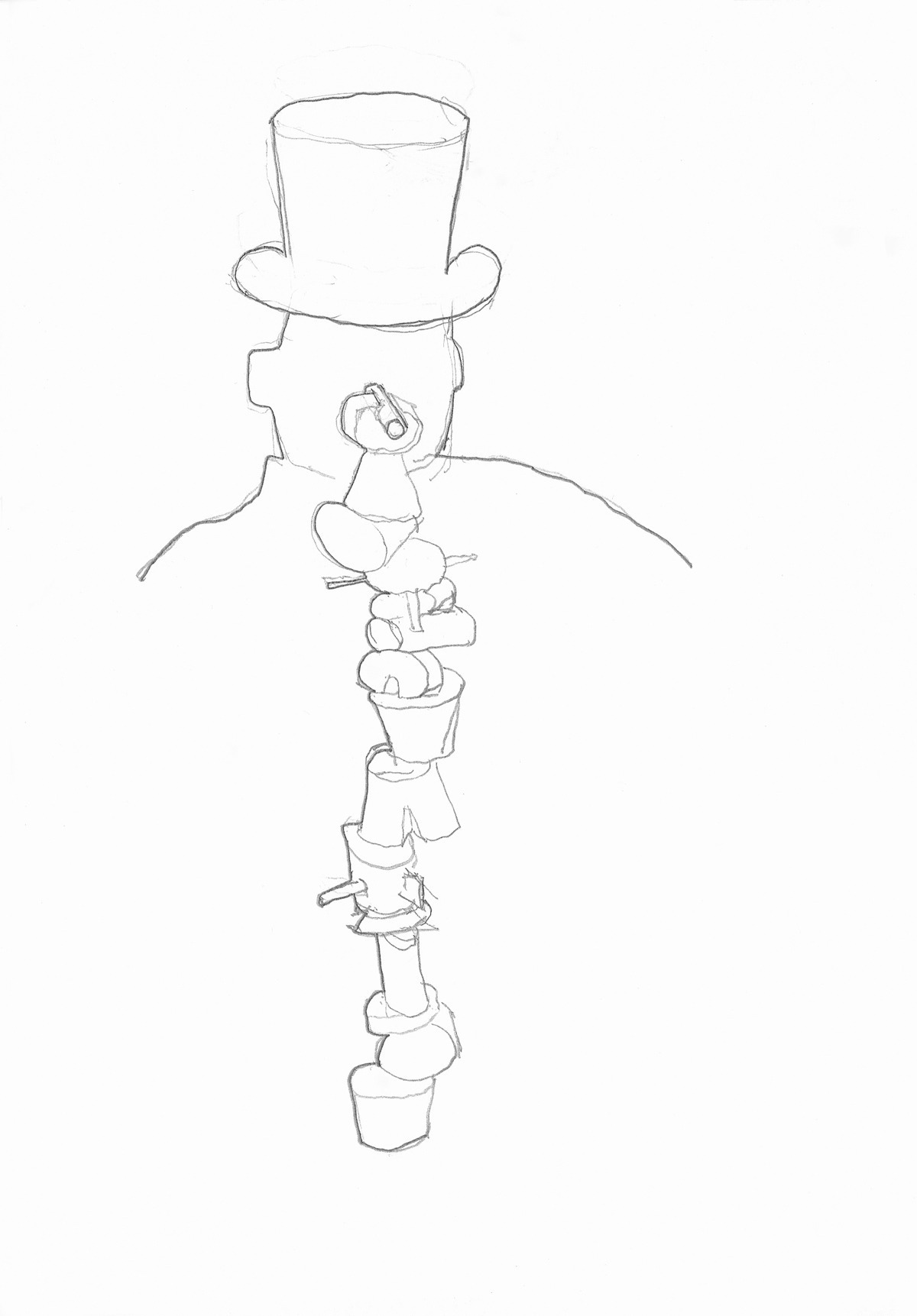

Notebook page showing stack schema, c. 1990

Untitled (Pillow) / 1997 / appx. 14″x14″x24″ / Cast plastic, plaster, paint

Stack (Repeater) / 1997 / appx. 9 x 9 x 24″ / Cast plastic, paint, metal and tape; steel (armature)

Lean / 1997 / appx. 9 x 9 x 38″ / Cast plastic, plaster and wax

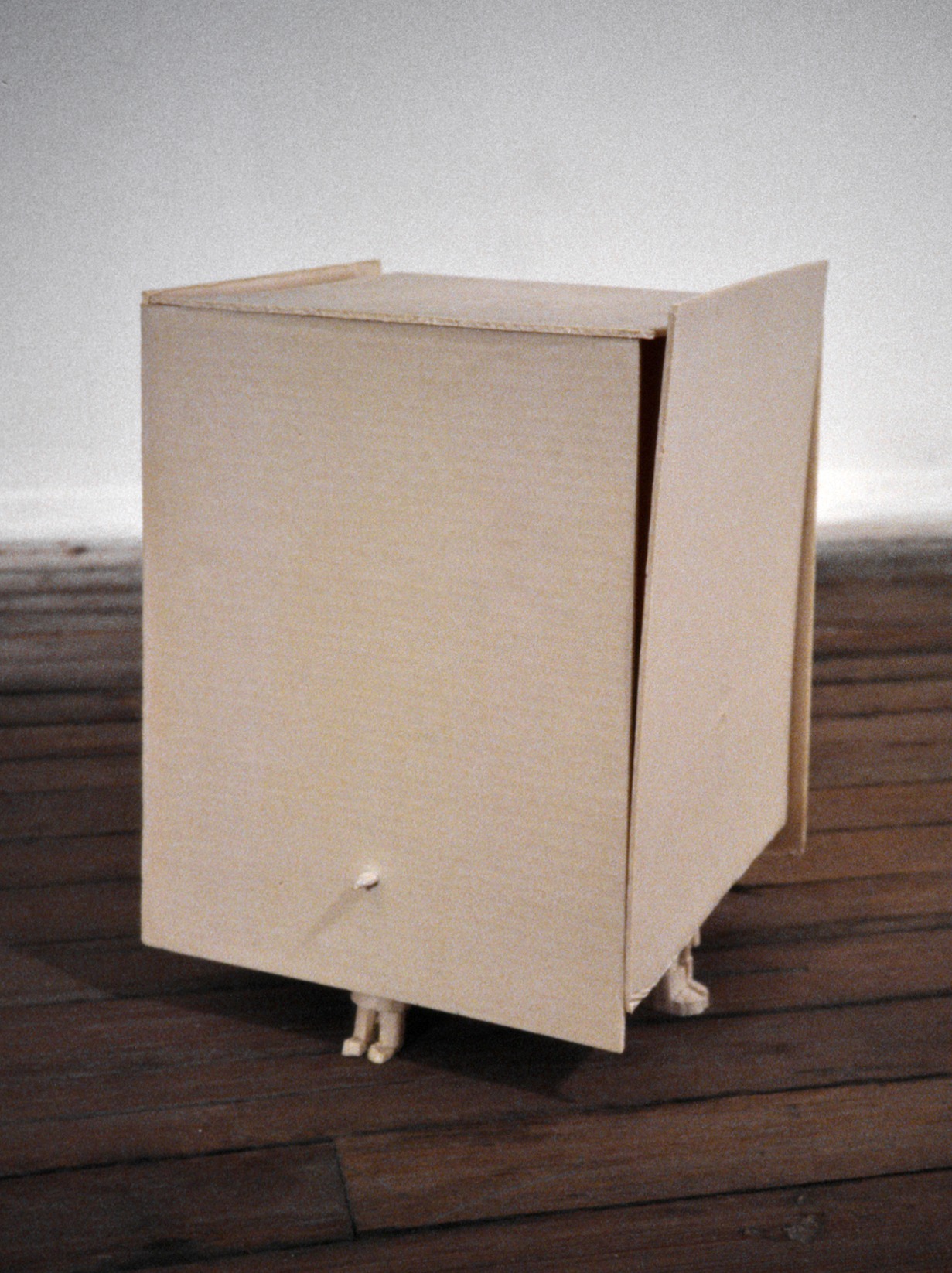

Cabinet / 1997 / appx. 14 x 9 x 9 (this variation) / Cast urethane

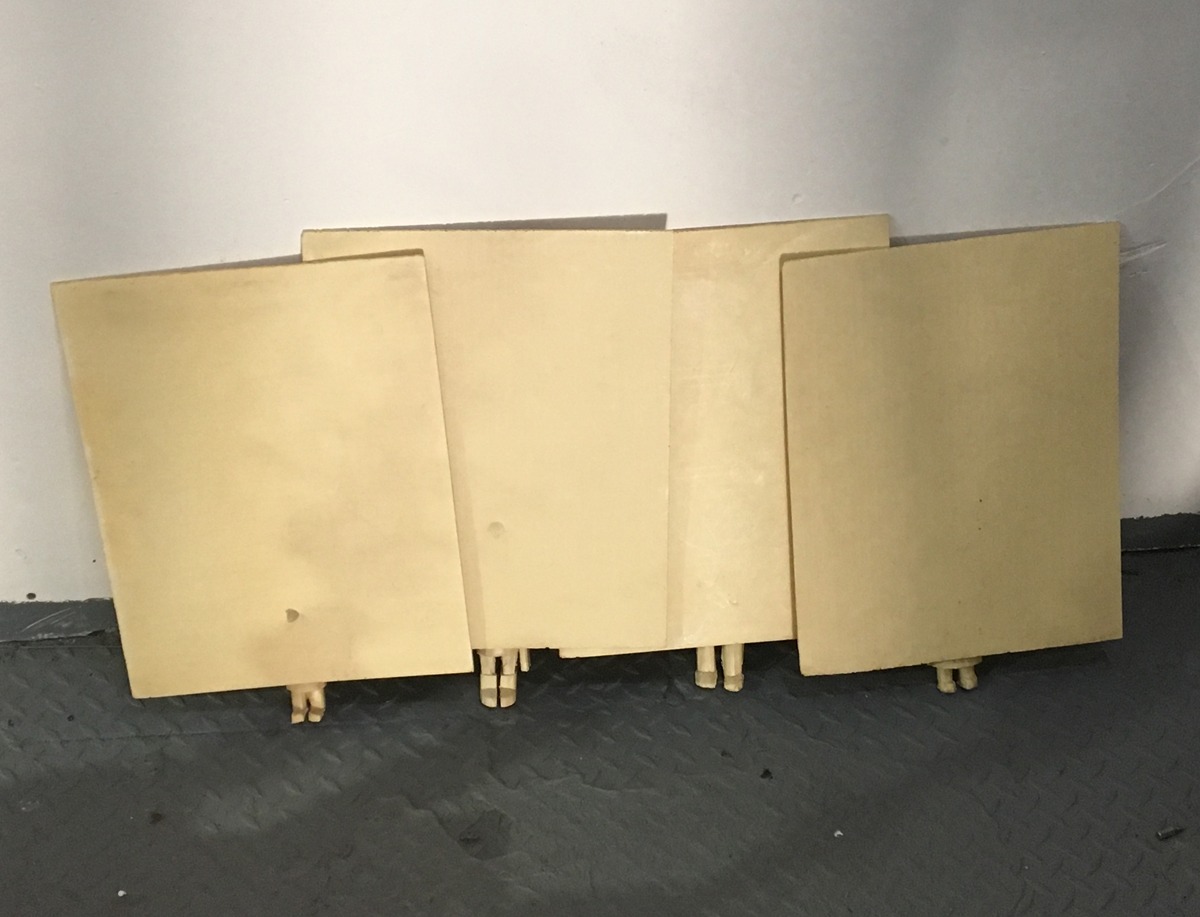

Cabinet (version) / 1997 (2000 arrangement) / Dimensions variable / Cast urethane

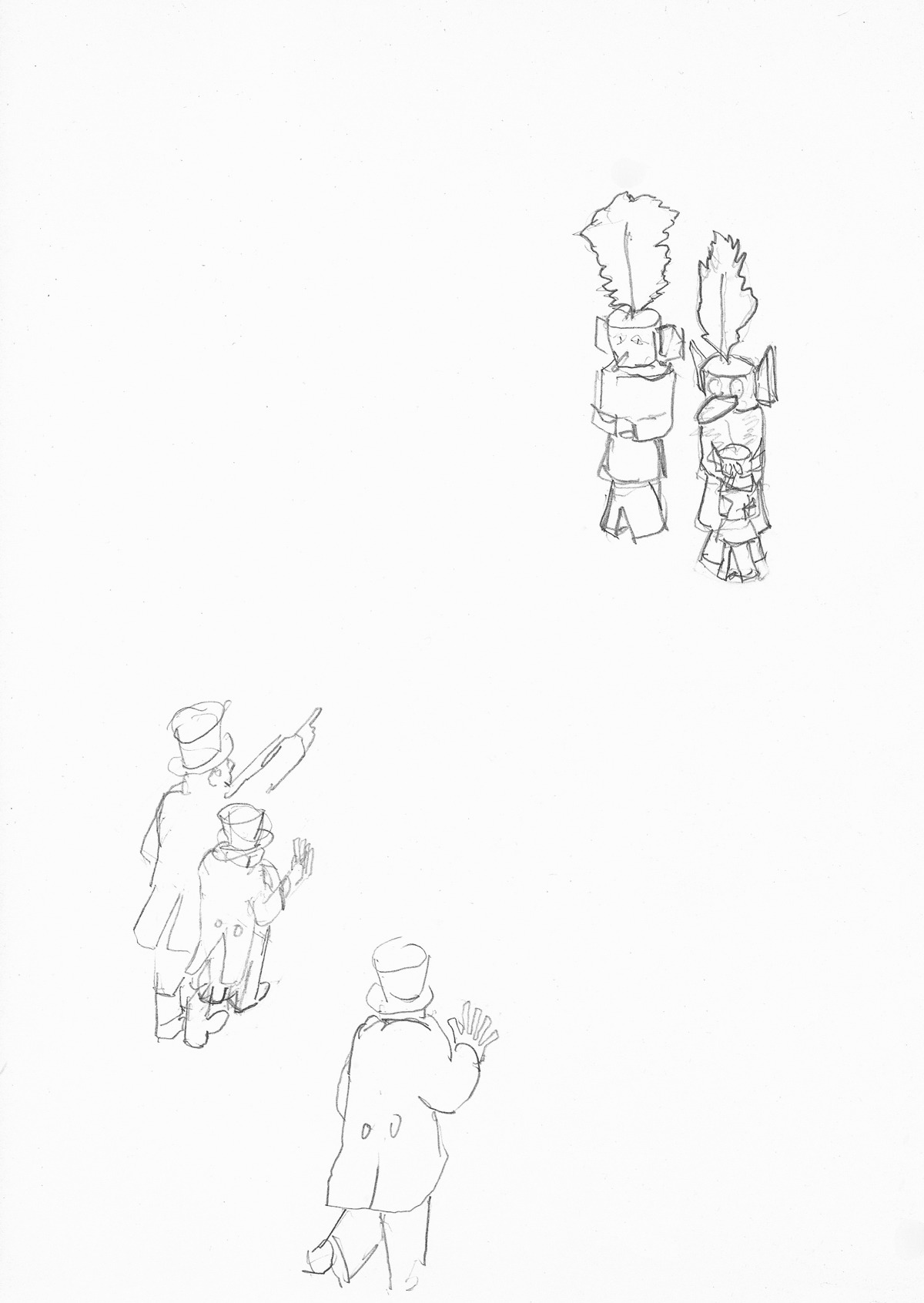

Across / 2006 / 9 x 12″ / Pencil on notebook page

Pinch / 2003 / 8 x 10″ / Pencil

Force / 2005 / 7″x10″ / Pencil on paper

Garland / 1997 / appx. 24 x 22 x 10″ / Cast plastic, plaster and paint

Untitled (Cabinet) / 1996 (recreated 2019) / Dimensions variable / Cast plastic, plaster and paint

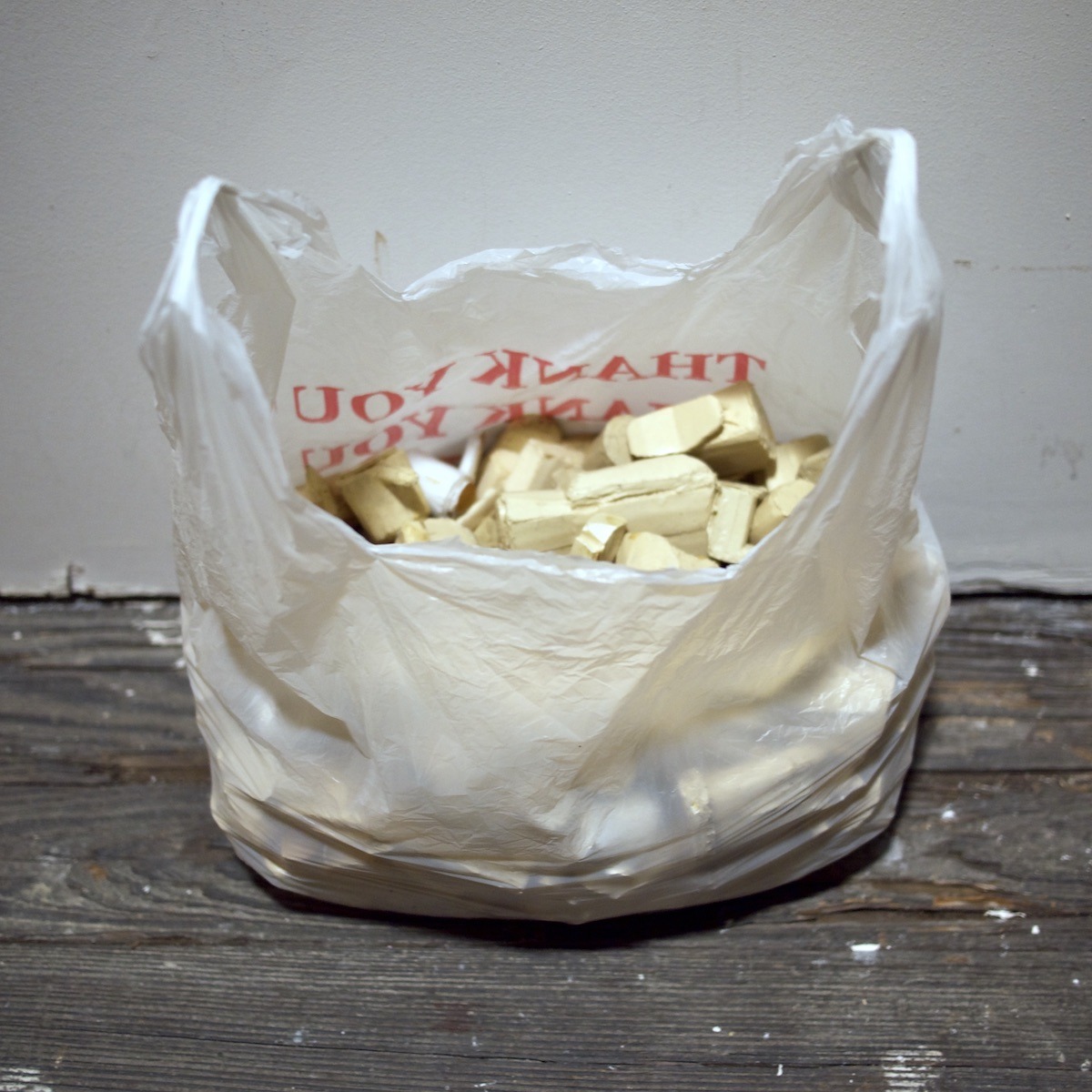

Untitled (Bag) / 2020 / Dimensions variable / Cast urethane in shopping bag

(continued)

I knew little about kachina dolls despite having had one since I was a kid. A sentimental attachment, a surviving remnant of childhood tied to some vague Romance of an open, mythic West witnessed through car windows while driving through.

My versions were made of bare, unpainted corrugated cardboard. I wasn’t using cardboard as an affront to taste, quality or permanence although it was sometimes read that way. It seemed neutral to me, without history, mute. I had been using it for years as a means to make easily built and easily torn down installation pieces about distance and place. When I made the dolls I left on the masking-or-color paper tape used to hold the cardboard forms together while the glue dried. It was a sort of stitching and moved between the purely structural and decorative. I didn’t always use it. The semi-transparent hot glue showed at exposed seams and joins. I wasn’t seeking a correspondence between materials and subject matter. I wanted difference.

I put clear varnish over everything, like sealing up a mummy. The pieces read as impermanent but weren’t really. Varnish makes distance.

When translating the doll over into cardboard I had without really thinking about it divided it up into discrete parts: feet, skirt, arms, torso and head/mask, building each part separately then piecing it back together. The doll I copied was a solid piece of wood excluding the ears and nose (and feather). I started jumbling the parts and standing them up vertically into what I called stacks. Early stacks went up via a sort of limited balance, each piece having to balance atop another without falling until being glued in place and secured with an armature. Stacks went up via scenarios, it was not improvised. I composed rules, repeating and/or distorting individual parts, inverting, reversing, extending. The pieces could end up looking rough, obsessive, expressive or aleatory, but these were side effects of how they were constructed. There was moderately cold reason and method behind my work, along with the steady part-by-part regularity of an assembly line. The stacks were reasonable aberrations and bore a striking resemblance to Modern sculpture.

I imagined I was the agent of a sideways social or cultural pressure that dissected and then tightly corseted the doll parts with tape, forcing the stacks upright and giving them shape. A barbarous late-Enlightenment-era scientist investigating and reanimating according to obscure logics with no regard of where the doll actually came from. A fantasy of Reason for the cause of Art, circling a knock-off curio. In the ’00s I drew bearded, beaver-hatted men in long formal tailcoats pointing, taunting and poking at the stacks with fingers or cigars. In one later drawing the men have taken on the cylindrical noses of the dolls by leaning in too close…the distortion is infectious).

The stacks to me seemed to be rising and falling (or about to fall) as they stood, an endless morphology. Forms were turning, becoming something else, moving. The pieces were supported by adjustable hidden armatures of plywood, screw stock, copper tubing and dowels, kept from toppling by dumbbell weights stuffed in the bases. Cardboard covered everything up. The armatures were a secret, a conspiracy of sorts that kept things standing, kept up appearances. They made the stacks into false-fronts, which I liked.

I placed the dolls and later the stacks on (repeated, distorted) Classical column bases scrupulously copied from books. These were first intended to act as frames and add some distance – to museumnify the objects I placed on them – being trite symbols of Culture and Timelessness. The dolls, stacks and bases were all made the same way but I was hoping the difference would be noticed. I stumbled upon texts about the relation of Classical Greek architecture to ritual sacrifice and symbolic enslavement, something that seemed to align with what I doing. One of the last kachina-related pieces was Garland where the stack has gone horizontal and hangs like draped entrails. The Classical base was exchanged for mundane (chair) legs.

Intentions and working metaphors could shift from piece to piece. In a deliberately over-didactic one-off bid to make it clearer to observers what I was actually doing, I copied, tripled and restacked the Koon’s Bunny, exchanging his hospital-grade stainless steel for container-class corrugated (Stack [Bunny]). Its base was of faux-wood patterned cardboard retrieved from a dumpster. I felt I was leading the rabbit away from end-traps, toward enigma and disaster. It was meant to be more of a loosening than a criticism.

I showed the bunny alongside kachina stacks at White Columns in 1990. Stack [Pressure] was for me a fairly straightforward picture of exchange. The parts diminished vertically and horizontally toward the middle, enacting a self-contained gravity that implied the piece (and maybe art in general) might gently suck into itself and disappear. (Stack [Remainder]) diminished as it went upwards in a false vertical perspective. Touching the 14’ ceiling, it stopped and then continued again up from the floor, an interrupted endless column. It was and wasn’t becoming architecture. Museum furniture.

In the early ‘90s I made a set of 7 non-generic kachina dolls based on images from books. I was forcing the issue and I now see these later dolls has having been dragged through the images in the books I copied them from, a making-real. I made molds of these dolls as well as a mold of a raw 9″x12″ cardboard sheet. I cast urethane, plaster and caster’s wax. I liked the remove that casting makes, a sort of petrification. The new materials seemed colder than the cardboard. I swapped out the Classical bases for pillows, boxes and furniture legs. The support and the subject merged as I eliminated the hidden armatures that had held the stacks up. Truth-to-materials seemed like a corpse worth poking (it actually never reanimated and the armatures returned). The tape went away but the colors of it were sometimes resurrected as paint. The jittering tapeforms were subsumed but they have shown up again in my recent paintings as tree trunks, true-cross pieces, wanderer’s legs, noses and pointing fingers. The cubes in the administrative paintings are kachina parts reduced to an easy neutral geometry.

The sale bin with figurines in it that I’d seen at the Brooklyn Museum – a bargain basement curio cabinet – resurfaced, distorted, in pieces like Cabinet from 1997.

In the ’90s I was thinking about appropriation as capture and one-sided exchange. In the end I started to hide the dolls or use only their feet and eventually I spirited them away. Ultimately what was left were cardboard boxes, cut ropes and furniture legs, all cast in plastic, the shell of an imaginary museum where all the entangled objects had been let go.